December 12, 2024

With this post, Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman reintroduces his Substack newsletter: Krugman wonks out. In the post, his first since retiring after nearly 25 years as a New York Times columnist, he discusses parallels between current and past efforts “to bring a business sensibility” to the federal budget, with the goal of eliminating inefficiency.

By Paul Krugman

First things first: welcome to readers new and old. Now that I have written my last column for the New York Times, this newsletter is coming out of dormancy. It will be mostly economics-related, and I’ll try to stay away from pure political punditry, although everything — including this post — is political these days.

This newsletter will be a lot wonkier than my Times column, and usually wonkier than my old Times newsletter. Definitely snarkier than either. I’ll try to stay fairly accessible, but may at times revert to academic-economist mode.

All posts will be free for a while, although I will eventually set up paid subscriptions for some content.

Short form thoughts will be appearing here.

(https://bsky.app/profile/pkrugman.bsky.social)

And with that, let’s get going.

Once upon a time a Republican president, sure that large parts of federal spending were worthless, appointed a commission led by a wealthy businessman to bring a business sensibility to the budget, going through it line by line to identify inefficiency and waste. The commission initially made a big splash, and there were desperate attempts to spin its work as a success. But in the end few people were fooled. Ronald Reagan’s venture, the President’s Private Sector Survey on Cost Control — the so-called “Grace commission,” headed by J. Peter Grace — was a flop, making no visible dent in spending.

Why was it a flop? There is, of course, inefficiency and waste in the federal government, as there is in any large organization. But most government spending happens because it delivers something people want, and you can’t make significant cuts without hard choices.

Furthermore, the notion that businessmen have skills that readily translate into managing the government is all wrong. Business and government serve different purposes and require different mindsets.

In any case, the Grace commission’s failure taught everyone serious about the budget, liberal or conservative, an important lesson: Anyone who proposes saving lots of taxpayer money by eliminating “waste, fraud, and abuse” should be ignored, because the very use of the phrase shows that they have no idea what they’re talking about.

OK, you know where this is going. There’s an obvious parallel between the Grace commission and Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, DOGE, led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. (The picture above is Leonardo Loredan, doge of Venice from 1501 to 1521, painted by Bellini.) But there are differences too: Muskaswamy bring a level of arrogant ignorance and clownish amateurishness that Grace never came close to emulating.

Grace, after all, assembled a staff of nearly 2,000 business executives divided into 36 task forces, who spent 18 months on the job, although they mostly came up empty. So far, at least, Muskaswamy don’t seem to be doing anything besides credulously scooping up random posts from social media.

Oh, and putting supervision in the hands of Marjorie Taylor Greene won’t help.

That said, there’s a pattern in their pronouncements so far, which I’d describe as Willie Sutton (the man who robbed banks because “that’s where the money is”) in reverse: going where the money isn’t.

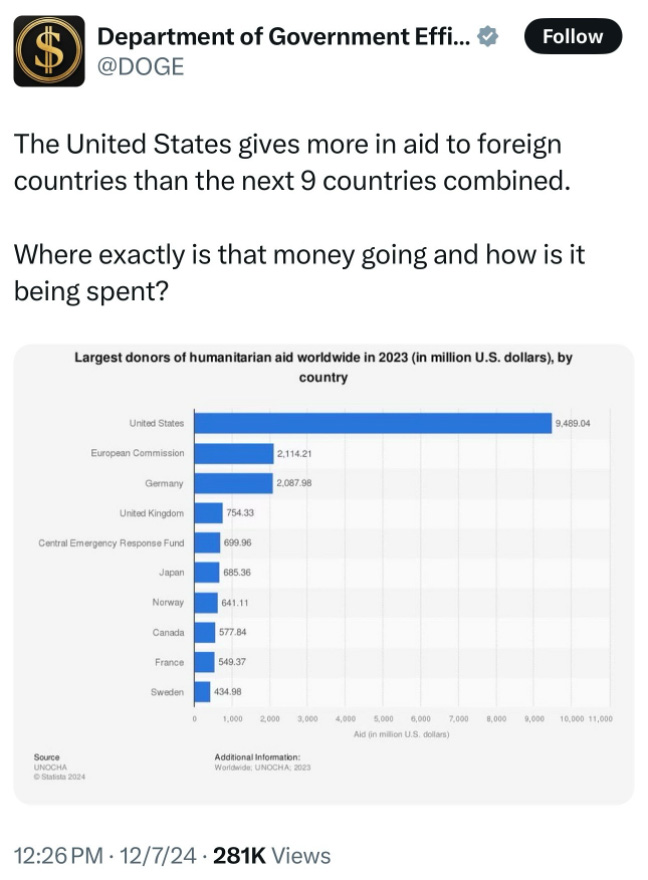

One of the first posts on DOGE’s Twitter account (of course it has a Twitter account) makes a classic, maybe the classic rookie error when talking about the federal budget, imagining that foreign aid is a significant expense:

Surveys consistently show that the public believes that foreign aid is around 25 percent of federal spending. But self-proclaimed budget experts should be aware that this is completely wrong; the true number is actually less than 1 percent.

Furthermore, whoever posted that chart didn’t bother to read the label. It’s not a chart of total foreign aid, just humanitarian aid — which is about one-sixth of one percent of federal spending. Overall, by the way, America spends a smaller percentage of GDP on foreign aid than the average advanced nation.

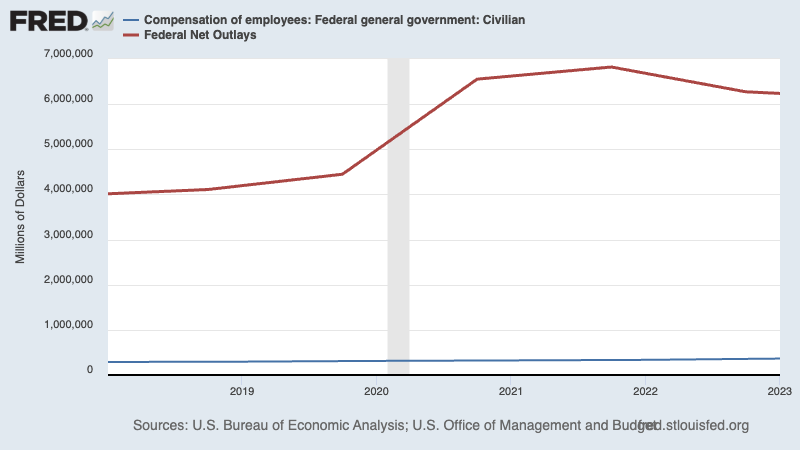

Moving on: In what I guess we should consider their opening manifesto, published in the Wall Street Journal, Muskaswamy call for “mass head-count reductions across the federal bureaucracy.” This suggests that they believe that bloated payrolls are a major budget issue. But how big a factor is employee compensation in federal spending? This big:

Again, going where the money isn’t.

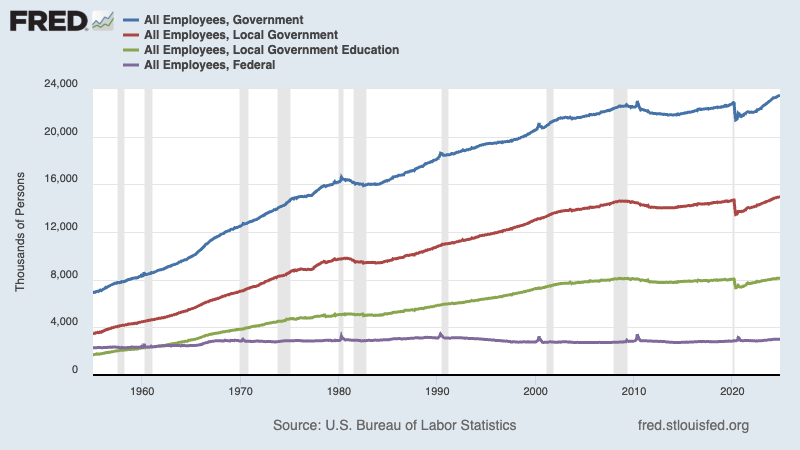

But wait: aren’t there tens of millions of Americans employed by the government? Yes, there are — but they overwhelmingly work for state and especially local governments, not the federal government DOGE is supposed to be tackling. In fact, federal employment is about the same now as it was in the 1950s:

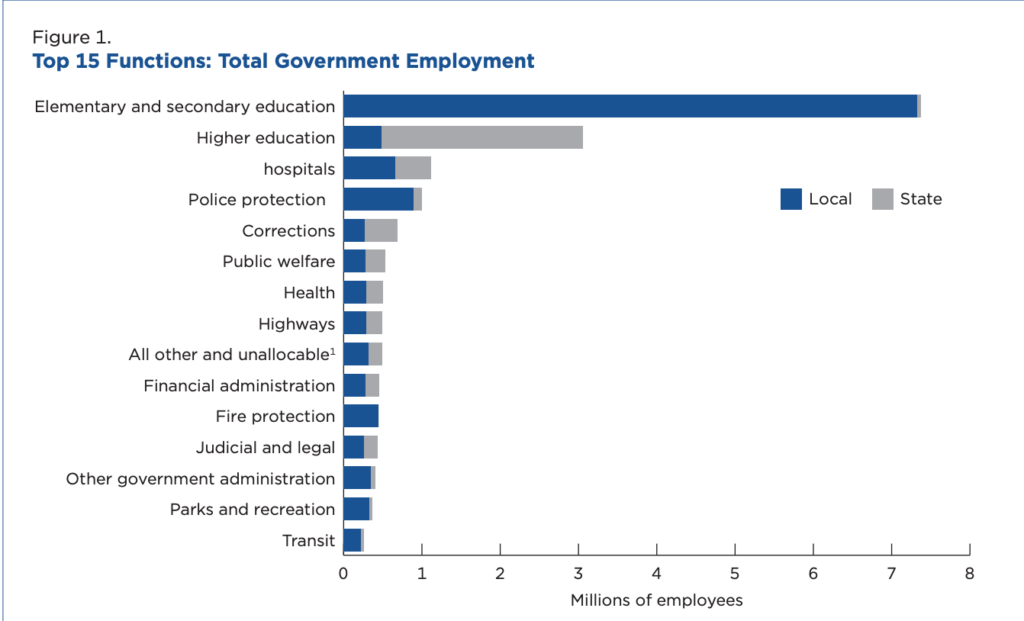

What are all those state and local workers doing? The Census offers a very useful chart:

The lion’s share of state and local employment is in education. Much of the rest is either in hospitals and other health care or in law enforcement. So when someone says “government worker” you shouldn’t imagine a paper-pusher in a cubicle — I mean, the government, like the private sector, does have lots of guys in cubicles, but they aren’t the typical employee. You should instead picture a schoolteacher, or maybe a nurse or a police officer.

But if the federal government doesn’t employ all that many people, why does it spend so much money?

Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality

Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality